Bacterial infections are the No. 1 cause of death in hospital patients in the U.S., and antibiotic-resistant bacteria are on the rise, causing tens of thousands of deaths every year. Understanding exactly how antibiotics work, or don’t, is crucial for developing alternative treatment strategies, both to target new “superbugs” and to make existing drugs more effective against their targets.

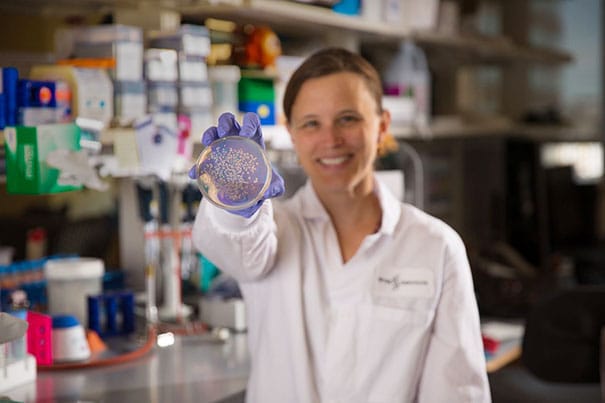

Using synthetic biology techniques, a team of researchers at the Wyss Institute at Harvard University has discovered that bacteria respond to antibiotics very differently – exactly opposite, in fact – inside the body than on a petri dish, suggesting that some of our current assumptions about antibiotics may be incorrect.

Bacterial studies are often carried out in vitro, but infections happen in the complex environment of living bodies, which are quite different from a petri dish. “If an antibiotic isn’t working, we should focus on finding ways to deliver more of it to the infection site or identifying other tolerance mechanisms that might be at play, rather than assuming that a bastion of nondividing bacteria is the culprit,” said corresponding author and Wyss core faculty member Jim Collins.

Comentarios recientes